Fascia consists of a solid part, a structure of fiber proteins, and a liquid part, a flow of water, hyaluronic acid, and other macromolecules.

Within the fascia it includes cells that produce the components that make up the fascia, such as fibroblasts that form fiber proteins and fasciacytes that produce hyaluronic acid. In fascia, however, all the body's cells are present, including immune cells and nerve cells.

When fascia is healthy, it produces hyaluronic acid—a substance that allows muscles and other tissues to expand, contract, and glide smoothly across one another. This fluid movement supports not only physical flexibility and ease but also allows the nervous system to function at its best.

However, when fascia becomes unhealthy, hyaluronic acid production diminishes, and tissues begin to stick together or adhere. These adhesions can cause pain, restrict mobility, and interfere with nerve function. Since the brain is in constant communication with the body, it registers these fascial restrictions as tension—tension that can ultimately hold emotional experiences due to stress, trauma or intense emotional events.

When the body experiences these states, the fascial tissue may tighten or constrict, creating areas of tension or restriction. Over time, unresolved emotional stress can cause the fascia to develop adhesions, reducing its elasticity and impairing its function, leading to further injury to the body.

These restrictions can manifest physically as:

This mind-body connection illustrates how emotional well-being and physical health are deeply intertwined. Just as physical injuries can impact emotional state, emotional trauma can manifest in physical structures—especially within the fascia.

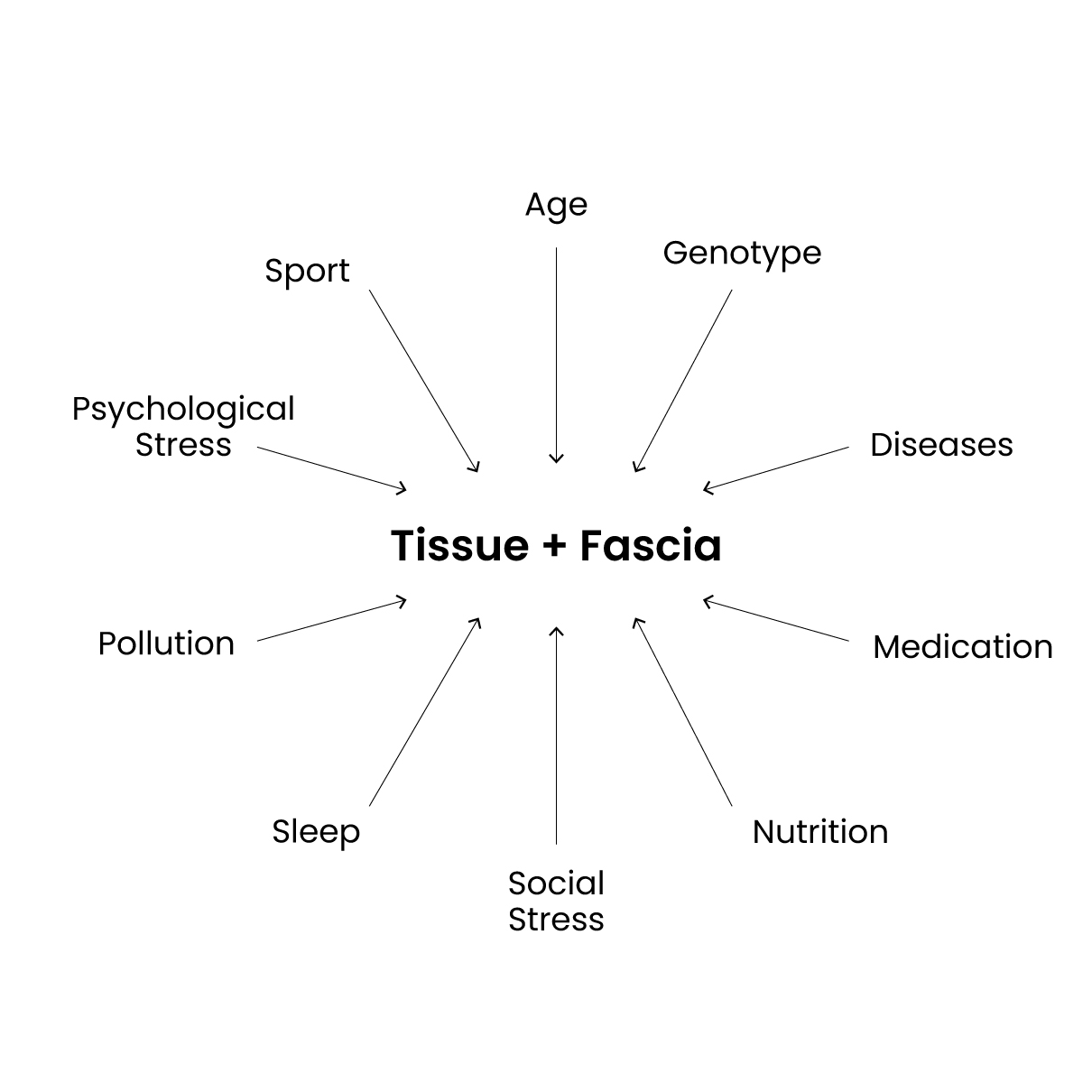

This represents what effects the fascia and what can be either a limiting or beneficial factor when treating the fascia.

Other factors to consider are the following.

These support fascia health or enhance fascial treatment outcomes:

These influences can impair fascia function or reduce the effectiveness of treatment:

Our body can be described as a collection of cells with different tasks; they are specialized to perform various types of work. For cells to be able to do their job, the transport of substances to and from the cells is required, such as nutrients and oxygen in and waste products out.

Cells must also be able to communicate with each other so that one cell knows what the others are doing. They do this in several ways, usually in combination, through chemical signals (neurotransmitters), mechanically (motion and pressure), via biophotons (light), and through weak electrical signals.

For all of this to work, something is needed in the space between all cells, something that also provides a communication pathway into the cells, via the cellular skeleton, to the cell nucleus that controls the cell - this is the fascia. Fascia ensures that cells are not loose like balls in a ball pit.

"We are a whole, a unit. Fascia is a living, vibrating, multidimensional [pressure-distributing network]. All our 35-75 billion

cells are embedded in this network. There are no gaps, no layers, only a continuous, dynamic network of soft material and cells, from head

to toe.

Suddenly, an accident occurs, and a wound forms. The unified network is forever changed, and our miraculous body/soul automatically shifts into self-healing mode, closing the hole and covering the opening with what we have learned since childhood, a scab.

The fantastic, pulsating, dynamic symmetry of [pressure distribution] and wholeness is interrupted by a patch. A living patch but a permanent break in symmetry".

Dr. Carol M. Davis, Professor Emerita of Physical Therapy, University of Miami.